Please note that all of these test scores were from classroom instruction before Covid-19. The scores came before the lockdown, before hybrid teaching, before disaster struck.

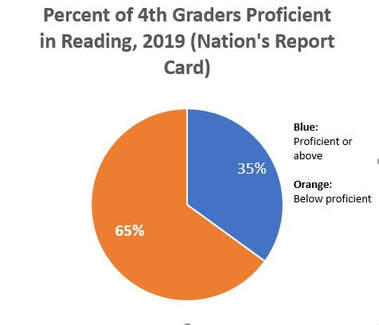

These scores show that more than half the students in every grade are struggling or even failing in reading. Reading failure is not a new problem. These students are often classified as “low performing” or “low achieving” readers. Although I do not like to place labels on children, knowing how reading specialists classify students does help us make comparisons.

- for 8th grade only 34% could read at or above grade level

- 12th grade only 37% could read at or above grade level

Reading Failure

The Nation’s Report Card shows that reading failure is a long-standing problem. As Peggy Carr from the assessments division for the National Center for Educational Statistics (NAEP) explains:

"Since the first reading assessment in 1992, there’s been no growth for the lowest performing students in either fourth or eighth grade…. Our students struggling the most with reading are where they were nearly 30 years ago.”

During these 30 years, whole language, phonics, and even balanced literacy have been the teaching methods used in the classroom. Classrooms across the nation continue to use these teaching methods, and it is these teaching methods that are causing students to fail.

You may be saying, “I don’t believe in test scores.” Then, how do you explain that reading scores were lower in 2019 than in 2017?

That’s right, we have more students who cannot read today than we did in 2017. If the teaching methods that we are using in the classroom were working and successfully helping students learn to read, then, even if test scores were biased or arbitrary, you would see an increase, even a modest increase in test scores. Instead, we see a decline in the number of students who can read at grade level.

Reading failure is a long-standing problem in the United States, and the problem is getting worse. We need to wake up before it’s too late. We need to change how we teach reading in the classroom. We need to stop screaming about the “reading wars” and ask ourselves “Why have we allowed students to fail for over 30 years?” If phonics, whole language, or even balanced literacy were effective, scores would not have been lower in 2019 than in 2017. The “reading wars” are ridiculous and should end; they did not help students in the least. A recent Washington Post article reviewed evidence that all three methods (phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy) are wrong and do not offer a solution to reading failure.

Giving an overview of the literacy problem in the United States, Rebecca Lake claims that approximately 20% of high school graduates cannot even read the words on their diploma as they put on their cap and gown and walk across the stage.

Reading Failure Is a Major Problem That Is Getting Worse. So, What Are We Going to Do about It?

If we simply send students back to the classroom and use the same teaching methods that were being used before Covid-19, we will send them back to a failing curriculum in reading.

Many schools announced that they introduced more phonics into their curriculum in 2019 than in 2017 and are clamoring that the “reading wars” are over and that phonics won.

If the “reading wars” are over, why did the students not win? Why are more than half of the students across the nation still failing?

Why Does Phonics Education Fail?

Earlier Post: We Are Using the Wrong Teaching Methods

So, where does this leave us? We have over half the students across the United States struggling or failing in reading. We have three teaching methods that have been proven not to work for the students who need the most help. Be careful. Do not be like some who claim that the struggling students can’t learn to read, and that regardless which method we use, “low achieving” students will never learn to read.

I have personally had the pleasure of helping many students learn to read:

- Students who failed under whole language in the school classroom have come to my after-school program, the Reading Orienteering Club, and returned to the classroom reading at their age level. Even if a student has been retained, we emphasize sending the child back to the classroom reading at their actual age level. Some children have moved up 4 grade levels in reading in one year.

- A group of students continued to fail after the school placed them in Reading Recovery, but the same students succeeded with my method of vowel clustering. They returned to the classroom reading at age level.

- Special needs students placed in a one-on-one pull-out program in systematic phonics still didn’t learn to read, but they came to my reading clinic and succeeded. They learned to read. I believe that every student can be taught to read.

- One student failed for nine straight years in reading but learned to read with vowel clustering teaching methods. The school had tried both balanced literacy and systematic phonics tutoring. Still, she failed. It’s never too late for a student to learn.

- Students who failed under “balanced literacy,” a common school program that combines whole language and phonics, also learned to read at age level using vowel clustering. We even had two students move up two grade levels in reading after only 48 hours of instruction with vowel clustering.

Why did one method succeed where phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy teaching methods had failed?

As David A. Kilpatrick explains in his book Equipped for Reading Success:

“Until recently, almost everyone thought that we store words by having some type of visual image of every word we know…. Many teaching approaches [like phonics and whole language] presume this. We assume that if students see the words enough, they will learn them. This is not true…. I believe this assumption that we store words based on visual memory is a major reason why we have widespread reading difficulties in our country…. The big discovery regarding orthographic mapping is that this oral “filing system” is the foundation of the “filing system” we use for reading words. We have no “visual dictionary” for reading that runs alongside our oral dictionary.” (pp. 59-68)

For a child to learn to read, the child must learn to match letters to the sounds they represent. This is not an easily learned task for some children. We need to use a teaching method that works with the oral language system and makes it easier for students to learn.

Therefore, phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy are never going to succeed with more than half of the students across the nation who cannot read at grade level because they are not being taught how to attach words to their oral language system. The vowel clustering teaching method that I use at my reading clinic works with the brain and helps struggling children learn to read.

We need change. The students desperately need for schools to adopt a new approach for teaching reading. Will they? Will the pandemic's end solve all our problems? Chester E. Finn, Jr., Distinguished Senior Fellow and President Emeritus, Thomas B. Fordham Institute, comments on this very question in his article, “How Ya Gonna Keep ‘Em Back in That Old School?”

“If the pandemic vanished tomorrow and all U.S. schools instantly reopened in exactly the same fashion as they were operating last February, how many parents would be satisfied to return their daughters and sons to the same old familiar classrooms, teachers, schedules and curricula? A lot fewer than the same old schools and those who run and teach in them are expecting back! Of course there’d be plenty of pent-up anger and frustration over the “lost year,” anxiety about kids struggling to catch up, … But would all that fade into gratitude for being able to resume the status quo ante? Nope. Some fading would doubtless happen over the months. But how many millions of families would insist on something different instead of docilely accepting schooling as it operated before the plague hit?”

Is Finn correct, will parents demand change? Will parents be satisfied to return to failed teaching methods? Will parents be content to see their children struggle?

How should we teach children to read?

We need to change and use a method that works, but will the schools make the change? Are the “reading wars” really over? We will continue to pursue this question in my next blog post.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed