In the 1960’s, educational theory swung back toward phonics, but then in the 1980’s, it turned back toward “whole-word,” which was quickly becoming known as “whole language.” In 2000, the National Reading Panel (NRP) was organized, supposedly to solve the question of which method was better. That was 21 years ago, and yet the battle rages on. The result of the NRP study was actually that most schools today have converted to balanced literacy—a combination of phonics and whole language. Balanced literacy has not proven to be any more successful than phonics or whole language.

Everyone claims that balanced literacy is new, but I myself learned back in the 50’s from a combination of phonics and the Dick and Jane readers (classified as whole language). Yes, they were awful. Unfortunately though, many students did not learn to read under that system in the 50’s. As one man explained to me, “they put me in a pullout phonics program every year from first grade on. It didn’t do any good. I still can’t read.”

Reading failure Is a Long-Standing Problem in the United States

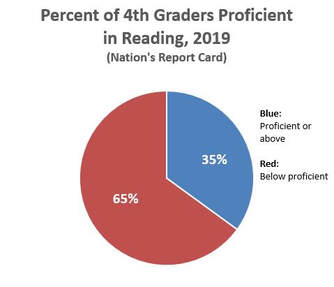

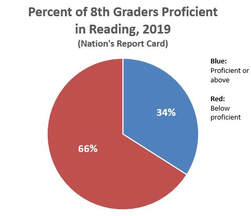

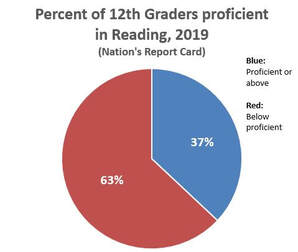

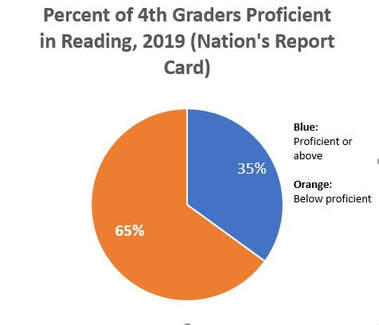

If we look at the Nation’s Report Card, we can quickly tell why the reading war continues. As these three pie charts illustrate (based on data from the 2019 Nation’s Report Card), reading failure is at an all-time high.

Keep in mind that all of these test scores were from classroom instruction before COVID-19. These scores reflect teaching methods used in classrooms before the coronavirus pandemic.

Although phonics enthusiasts claim that they have won the reading war, the war rages on because students continue to fail.

Notice that I did not say it is teachers, parents, poverty, or lazy students who are responsible for reading failure. No, it is the teaching methods that we are using in the classroom to teach students how to read—the curriculum. Phonics and whole language simply do not work.

Yes, I’m certain that the teaching methods being used in the classroom are the cause of reading failure. I run a free reading clinic for at-risk and failing students. I staff my reading clinic with volunteers who have only minimal training at best. Most of our students are failing in reading when they walk in the door in September. They have been taught in the school classroom with phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy. When they complete my program in May, they are able to read; some have even advanced four grade levels in reading, just from September to May. I also had an undergraduate student direct the program one year, and she had children move up three grade levels in reading. So, yes, the problem is the curriculum and the teaching methods that we are using in the school classroom. If we want to stop reading failure, then we must stop bickering and get rid of phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy. It’s time for us to adopt a new approach to teaching reading, an approach that works for all students.

Earlier Post: Curriculum Choices Determine a Student's Success or Failure in School

The Reading Wars Have Contributed to Reading Failure

Reading failure is not a new problem, but it has been growing lately. Peggy Carr, associate commissioner from the assessments division for the National Center for Educational Statistics (NAEP) explains quite graphically that failure in reading has been raging throughout the reading wars.

“Since the first reading assessment in 1992, there’s been no growth for the lowest performing students in either fourth or eighth grade…. Our students struggling the most with reading are where they were nearly 30 years ago.”

As Carr went on to explain, reading scores are getting worse. We have more students who cannot read today than we did in 2017. Yet, schools are saying that they have included more phonics into their reading programs. Obviously, phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy have all failed to help students who need the most help in learning to read. Carr states:

"Eighth grade is a transitional point in preparing students for success in high school, so it is critical that researchers further explore the declines we are seeing here, …. Both low- and high-achieving eighth graders slipped in reading, but the declines were generally worse for lower-performing students.”

The reading wars have solved nothing. Switching back and forth from phonics to whole language and from whole language back to phonics has not helped students learn to read. Although phonics enthusiasts have been shouting that the reading wars are over and that phonics won, more and more students continue to fail in reading.

Did Jeffrey Bowers Just Reignite the Reading Wars?

Jeffrey S. Bowers, professor at the University of Bristol’s School of Psychological Science, Bristol Neuroscience has just reignited the battle over phonics.

The problem, as Bowers explains, is that we cannot expect phonics, whole language, or balanced literacy to help struggling students learn how to read.

That’s right; none of these methods really work with students who need the most help which leaves over half of the students across the nation struggling or failing.

Bowers’ 2020 research article, set off a firestorm of responses from the phonics camp. The war is raging hotter than ever, but this time instead of just trading theories back and forth, research scientists are looking at the actual data that phonics advocates claim supports their theory. The data isn’t holding up.

As Dr. Bowers continues to clarify in his latest 2021 article,

“The strength of evidence for phonics has been exaggerated in some circles, …. And that is why it is so important to recognize that the evidence for phonics is weak: it should motivate researchers to look beyond the phonics/whole language debate.… My position is that although there is indeed good evidence that teaching GPCs [grapheme-phoneme correspondence] is essential, there is little evidence that phonics is effective, either by itself or in combination with other forms of instruction. My conclusion is that more research should be carried out on alternative approaches….” (pp. 3-4)

Bowers is not arguing that "grapheme phoneme correspondence" (the process of relating alphabet letters to oral sounds) is important and even essential. Instead, Bowers is saying that the evidence most phonics believers are quoting as proving that phonics works does not exactly say what they claim. The evidence is weak, and this is one of the reasons that so many students are not learning to read. Phonics is simply not as effective a teaching method as they claim.

One phonics advocate, Jack M. Fletcher, in his response to Bowers even admitted that “some researchers have exaggerated the strength for phonics.”

Wait just a minute, weren’t the phonics experts just telling us how great phonics is and how it will solve all of our problems even though over 60% of students across the nation haven’t been able to read at grade level in 4th, 8th, or 12th grade since 1992?

Now, they want to backtrack and admit that some researchers have overstated the effectiveness of phonics.

I agree with Bowers. We need to dump phonics, whole language, and balanced literacy and look for a totally new method for teaching students to read.

National Reading Panel Data Gives Us Concerns

Bowers is not the only person explaining that the case for phonics should not rely on the data from the NRP. In 2006, Gregory Camilli from Rutgers along with his research team also reanalyzed the data from the NRP study. As Camilli stated, systematic phonics “is generally considered a weak intervention.”

Similarly, Jon Reyhner, Department of Education Specialties at Northern Arizonia University, explains the problem in his 2020 article entitled The Reading Wars [Reyhner pulls passages directly from the National Reading Panel (NRP) report and cites page numbers from the full NRP book].

“Despite a phonics predisposition, the NRP concluded that ‘phonics instruction produces the biggest impact on growth in reading when it begins in kindergarten or 1st grade before children have learned to read independently’ and it ‘failed to exert a significant impact on the reading performance of low-achieving readers in 2nd through 6th grades’ (NRP, 2000, pp. 2-93-94). The NRP also noted that ‘it is important to emphasize that systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction to create a balanced reading program. Phonics instruction is never a total reading program.... Phonics should not become the dominant component in a reading program, neither in amount of time devoted to it nor in the significance attached" (p. 2-97).

Educational psychologist Gerald Coles believes that the NRP actually did a disservice to struggling students because it sounded as if they had an answer, but they failed to deliver a solution to the students who were failing and needed the most help.

In all fairness, if you read the entire report, the NRP did state that “… phonics instruction failed to exert a significant impact on the reading performance of low-achieving readers in 2nd through 6th grades….” (p. 94).

In essence, the NRP is admitting that you only see improvement the first year or two with phonics training. This improvement does not carry over into third, fourth, or fifth grade, and the statistical significance all but disappears by sixth grade. So, how can phonics be classified as an effective teaching method? As a matter of fact, when phonics has been compared directly to another teaching method, phonics has not scored well.

For example, Sebastian P. Suggate’s 2016 study compared 71 phonemic and phonics intervention groups and found that “… phonemic awareness interventions showed good maintenance of effect… phonics tended not to.” In other words, the phonemic awareness teaching method was better than the phonics teaching method for helping children learn how to read.

In my own research, I compared the effectiveness of vowel clustering teaching methods in a group-centered prevention structure against phonics in a one-on-one tutoring setting. The students being taught using vowel clustering outscored the students being taught phonics through one-on-one tutoring. In follow-up testing one year later, the students from my Camp Sharigan program were still ahead of the students being taught phonics. Camp Sharigan is only a one-week program.

The fact that phonics has problems is not news. Over the years, numerous phonics advocates have also warned about the shortcomings of phonics. In 2001, Linnea C. Ehri, a strong phonics supporter, admitted that phonics would “not help low achieving readers.” Jeanne Sternlicht Chall, as far back as 1967, warned that phonics would not work for all students. So yes, Fletcher is correct: many enthusiastic newspaper reporters, Internet bloggers, and even some researchers have exaggerated and overstated the case for the effectiveness of phonics. Phonics simply does not work for many students, especially struggling students. The students who need help the most.

Earlier Post: Why Does Phonics Education Fail?

Instead of fighting over phonics and whole language, we need a totally new method for teaching struggling students how to read.

It is time to stop bickering and find a new teaching method. No, balanced literacy is not the answer either. We need a new teaching method that helps students link reading with the oral language system.

Mark Seidenberg clearly states in his book, Language at the Speed of Sight: How We Read, Why so Many Can’t, and What Can Be Done About It, that the way we teach reading is “a significant part of the literacy problem.”

Seidenberg goes on to point out three main problems with our present teaching methods

- current teaching practices are based on outdated assumptions.

- true scientific research in reading has had very little effect on how reading is taught in the classroom.

- new neurobiological brain research in reading is being totally ignored by today’s educators.

Dr. Seidenberg goes on to point out that we have decades of research showing that the only effective way to teach children to read is to teach skills that connect reading with oral speech. So, why are we arguing over phonics and whole language when neither of those methods connect to oral speech?

We’ll talk more about the importance of the oral language system for learning to read next time, but for now I want to close with a quote from Dr. Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases for over 35 years. Dr. Fauci was speaking about scientific research and opinions in reference to the coronavirus pandemic, but I believe that his comment about research and opinions is equally valid for the reading wars.

“People’s opinions are a fact of life. What gets, um, I think troublesome, is when people develop their own set of facts. Facts don’t change. So you have a different opinion, but facts are consistent. That’s the problem.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed